Baumgarten House

3450 McTavish Street, Montreal, Quebec

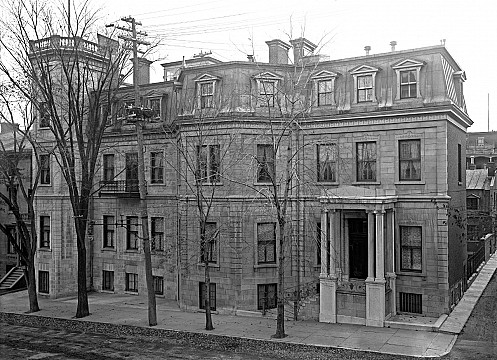

Built from 1884, for Alfred Baumgarten (1842-1919) and his wife, Martha Christina Donner (1866-1953). First impressions can be deceptive: the austere formality of the exterior of this house hides what the author Donald MacKay so brilliantly called, an interior "not unlike a set for a Ruritanian light opera". Aside from the ballroom with its unique spring-loaded floor, this was the first house in Montreal with an indoor swimming pool and the first in Montreal - not to mention among the first in the world - to generate its own electricity. A cultured, jovial, broad-minded, quintessential host, Baumgarten was not a Baron as legend likes to allude to, but he certainly lived like one....

This house is best associated with...

Alfred Baumgarten was born to a distinguished medical family in Germany. He grew up around the household of King Albert of Saxony to whom his father was Court Physician while his mother (a childhood friend of the famous composer Richard Wagner) was Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Carola. He came to Montreal via New York and succeeded his wife's uncle as President of the Saint Lawrence Sugar Refinery in 1895. He was Life Governor of the Montreal General Hospital and was reckoned to be the largest shareholder in the Bank of Montreal. As a host, he was popular, generous and jovial. He relished entertaining and almost certainly took the greatest pleasure in his role as Master of the Montreal Hunt.

In 1885, Alfred married Martha Donner, 25-years his junior and a great-granddaughter of Conrad Hinrich Donner who founded the Donner & Reuschel Bank at Hamburg in 1798. In the same year they were married, Alfred commissioned an unknown architect to build their marital home with a facade loosely modelled on Martha's ancestral pile back in Germany, Donner's Park. Fronting McTavish Street, back from Sherbrooke Street, it replaced three of the eight houses that once constituted Rupert's Terrace and on completion stood three stories high over a generously raised basement, flanked by a four-story tower. Not including kitchens and servants quarters, it covered 15,800-square feet.

Upscale Living in Downtown Montreal

In a world dominated by Scots and Northern Irish, Baumgarten was an unusual figure among Montreal's business elite and his house was as unusual to them as his background. The reception rooms were not confined to the ground floor, they were split across two levels, and just as he had borrowed elements from his wife's past for its exterior, it's entirely plausible that he delved into his own family history for what some perceived to be its sometimes eccentric interior. Either way, compared to his more socially conservative neighbors, he was far less concerned about conforming to norms.

The house opens into an oak-panelled vestibule with a mosaic floor that leads into the mahogany-panelled entrance hall where the softness of the green rug underfoot was in contrast to the battle-hardened suits of medieval armour that hung guard on its walls.

To the south of the hall is what the Baumgarten's referred to as their "Living Room". It was divided into two distinct halves, neither of which aspired to be "a period room" but were focused entirely on comfort and informality - or at least as much informality as a millionaire and leader of society could muster back then. The rich, oak-panelled fireside half festooned with velvet sofas was distinctly 'male' and reminiscent of a cosy corner of a gentleman's club; while, the lighter, brighter and altogether more elegant windowed half was undoubtedly 'female'. The silk-lined walls were woven in soft reds and golds while the floor was covered entirely by an Indian rug exquisitely tapestried in discrete reds, blues and yellows. Being Continental, the Baumgartens were less inclined than their British counterparts to separate the sexes, which to many a stick-in-the-mud Presbyterian back then would have been as radical as if they'd declared the room to be "gender fluid".

Directly above the Living Room is the library. The lower half of its walls were covered with dark-oak bookcases while above they were lined in dark blue chintz under a heavily corniced ceiling of mellow gold. A thick Persian rug lent itself to the colour scheme and an aged terra cotta fireplace kept Baumgarten warm as he worked on papers and patents.

Downstairs, to the west of the Living Room was the Dining Room, another magnificently panelled room in richest, intricately carved mahogany under a Tudor-style coffered ceiling. An editorial from the time quite rightly described "each bit (as) a work of art" and it seems that rooms like this were a matter of pride to Montreal's elite, as if to demonstrate first-hand the richness it was possible to attain from their densely forested country. The subdued elegance of the room was added to by a pair of centuries-old tapestries - custom-framed within the mahogany panelling - that depicted ancient hunting scenes, while under foot, fidgeting feet were laid to rest on, "a very heavy hand-tufted Donegal rug".

Table Tally-Ho

In 1904, the Dining Room was the scene of a hunt dinner over which Baumgarten, the former Master, presided. Stretching the length of the table (see images), it featured an award-worthy decoration: Over a countryside scene crafted from grass, moss, and twigs - plus its own babbling brook - rode cardboard cut-out figures of huntsmen on horseback (made individually recognisable by Baumgarten's close friend, hunt member, and equine artist Leopold Galarneau) in hard pursuit of a fox seen darting out through an open gate.

Springs & Swimming Pools

Baumgarten's private passions were fox-hunting and ballroom dancing. Founded in 1826, the Montreal Hunt remains the oldest of its kind still in existence in North America, but it wasn't until 1882 when Baumgarten became Master of the Hunt that his drive and dollars elevated the Meet from a mere seasonal "frolic" to a prestigious club. His first undertaking was to construct a new clubhouse on Delorimier Avenue, and to his own design, the 45-foot ballroom there rested on a bed of Pullman springs to give the dancers - quite literally - an added spring to their step; and, after the club moved to new premises in 1898, he moved the dance floor into his own ballroom ready for his daughters' debutante seasons.

Occupying the south side of the house, the buff-coloured, white-trimmed ballroom is punctuated by four Sienna marble columns that support the delicately vaulted, lit ceiling. Hugging the walls were positioned carved oak benches upholstered with rose and white tapestries that matched the silk hangings. At one end, wide, shallow steps descend into the room from the Living Room, while at the other end, underneath the minstrel's gallery - suspended from the ceiling by brass cords as if to float - a flight of mahogany stairs once lined with thick Persian carpet lead up to the two-story Gothic Gallery, the foot of which was flanked on either side by a pair of matching consul tables under French gilt mirrors.

The other feature added by Baumgarten for the clubhouse and then replicated for his own home was the indoor pool. Situated on the chamber (bedroom) floor of his mansion, and also sometimes referred to as a sunken bath, it measured 15-feet-by-25-feet with a depth of 8-feet, and was complete with fox masks (heads) for faucets. Aside from centrally-heated towel rails, the blue-and-white tiled room was warmed by its own open fireplace.

The Gothic Gallery

The fantastical Gothic Gallery directly over the ballroom might easily have been a stage set for Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal - and that isn't as outlandish as it may sound because of course Baumgarten's mother, Emmy, was a childhood friend of the great composer, and there's every chance that Baumgarten remembered him from his time in Dresden.

The room was designed to be a romantic and informal place for couples and groups to relax between and after dances. Spanning two full stories it is topped by a skylight that bathed the room in soft yellows, ambers and golds. The lower half is centred by a double-sided fireplace around which the elaborate mahogany staircase wound its way up to the gallery. The vaulted ceilings on both floors were propped up by Gothic pillars, and coupled with the exquisite Gothic carvings in both stone and wood (notably the arched doorways and five similar cabinets), the whole was worthy of any Medieval castle or abbey.

A Favorite of the Governors-General

To gain some insight into the social hierarchy of Montreal in the 1880s, one has to look no further than the Tandem Club: who occupied which sleigh; with whom; and, in which order they progressed. In February 1884, R.B. Angus followed Andrew Allan (both driving four-in-hands) who was behind Baumgarten in his "magnificent" four-in-hand in which he was driving the future Earl and Countess of Minto, while they were led from the front by Lord and Lady Lansdowne's sleigh - the most magnificent, of course.

Baumgartens's ease around - and understanding of - the aristocracy, coupled with his generous nature and cultured mind made him a firm favorite with Landowne and Minto. Choosing to stay here over taking apartments at the Windsor Hotel, the Lansdownes (who already "entered fully into the life of the Montreal Hunt") stayed for ten days in January, 1887, and for a further week the following month during the Winter Carnival. By the time the Earl of Minto was appointed Governor-General of Canada in 1898, he warmly referred to Baumgarten as, "my old friend," and relished his invitations to McTavish Street.

In 1885, Alfred married Martha Donner, 25-years his junior and a great-granddaughter of Conrad Hinrich Donner who founded the Donner & Reuschel Bank at Hamburg in 1798. In the same year they were married, Alfred commissioned an unknown architect to build their marital home with a facade loosely modelled on Martha's ancestral pile back in Germany, Donner's Park. Fronting McTavish Street, back from Sherbrooke Street, it replaced three of the eight houses that once constituted Rupert's Terrace and on completion stood three stories high over a generously raised basement, flanked by a four-story tower. Not including kitchens and servants quarters, it covered 15,800-square feet.

Upscale Living in Downtown Montreal

In a world dominated by Scots and Northern Irish, Baumgarten was an unusual figure among Montreal's business elite and his house was as unusual to them as his background. The reception rooms were not confined to the ground floor, they were split across two levels, and just as he had borrowed elements from his wife's past for its exterior, it's entirely plausible that he delved into his own family history for what some perceived to be its sometimes eccentric interior. Either way, compared to his more socially conservative neighbors, he was far less concerned about conforming to norms.

The house opens into an oak-panelled vestibule with a mosaic floor that leads into the mahogany-panelled entrance hall where the softness of the green rug underfoot was in contrast to the battle-hardened suits of medieval armour that hung guard on its walls.

To the south of the hall is what the Baumgarten's referred to as their "Living Room". It was divided into two distinct halves, neither of which aspired to be "a period room" but were focused entirely on comfort and informality - or at least as much informality as a millionaire and leader of society could muster back then. The rich, oak-panelled fireside half festooned with velvet sofas was distinctly 'male' and reminiscent of a cosy corner of a gentleman's club; while, the lighter, brighter and altogether more elegant windowed half was undoubtedly 'female'. The silk-lined walls were woven in soft reds and golds while the floor was covered entirely by an Indian rug exquisitely tapestried in discrete reds, blues and yellows. Being Continental, the Baumgartens were less inclined than their British counterparts to separate the sexes, which to many a stick-in-the-mud Presbyterian back then would have been as radical as if they'd declared the room to be "gender fluid".

Directly above the Living Room is the library. The lower half of its walls were covered with dark-oak bookcases while above they were lined in dark blue chintz under a heavily corniced ceiling of mellow gold. A thick Persian rug lent itself to the colour scheme and an aged terra cotta fireplace kept Baumgarten warm as he worked on papers and patents.

Downstairs, to the west of the Living Room was the Dining Room, another magnificently panelled room in richest, intricately carved mahogany under a Tudor-style coffered ceiling. An editorial from the time quite rightly described "each bit (as) a work of art" and it seems that rooms like this were a matter of pride to Montreal's elite, as if to demonstrate first-hand the richness it was possible to attain from their densely forested country. The subdued elegance of the room was added to by a pair of centuries-old tapestries - custom-framed within the mahogany panelling - that depicted ancient hunting scenes, while under foot, fidgeting feet were laid to rest on, "a very heavy hand-tufted Donegal rug".

Table Tally-Ho

In 1904, the Dining Room was the scene of a hunt dinner over which Baumgarten, the former Master, presided. Stretching the length of the table (see images), it featured an award-worthy decoration: Over a countryside scene crafted from grass, moss, and twigs - plus its own babbling brook - rode cardboard cut-out figures of huntsmen on horseback (made individually recognisable by Baumgarten's close friend, hunt member, and equine artist Leopold Galarneau) in hard pursuit of a fox seen darting out through an open gate.

Springs & Swimming Pools

Baumgarten's private passions were fox-hunting and ballroom dancing. Founded in 1826, the Montreal Hunt remains the oldest of its kind still in existence in North America, but it wasn't until 1882 when Baumgarten became Master of the Hunt that his drive and dollars elevated the Meet from a mere seasonal "frolic" to a prestigious club. His first undertaking was to construct a new clubhouse on Delorimier Avenue, and to his own design, the 45-foot ballroom there rested on a bed of Pullman springs to give the dancers - quite literally - an added spring to their step; and, after the club moved to new premises in 1898, he moved the dance floor into his own ballroom ready for his daughters' debutante seasons.

Occupying the south side of the house, the buff-coloured, white-trimmed ballroom is punctuated by four Sienna marble columns that support the delicately vaulted, lit ceiling. Hugging the walls were positioned carved oak benches upholstered with rose and white tapestries that matched the silk hangings. At one end, wide, shallow steps descend into the room from the Living Room, while at the other end, underneath the minstrel's gallery - suspended from the ceiling by brass cords as if to float - a flight of mahogany stairs once lined with thick Persian carpet lead up to the two-story Gothic Gallery, the foot of which was flanked on either side by a pair of matching consul tables under French gilt mirrors.

The other feature added by Baumgarten for the clubhouse and then replicated for his own home was the indoor pool. Situated on the chamber (bedroom) floor of his mansion, and also sometimes referred to as a sunken bath, it measured 15-feet-by-25-feet with a depth of 8-feet, and was complete with fox masks (heads) for faucets. Aside from centrally-heated towel rails, the blue-and-white tiled room was warmed by its own open fireplace.

The Gothic Gallery

The fantastical Gothic Gallery directly over the ballroom might easily have been a stage set for Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal - and that isn't as outlandish as it may sound because of course Baumgarten's mother, Emmy, was a childhood friend of the great composer, and there's every chance that Baumgarten remembered him from his time in Dresden.

The room was designed to be a romantic and informal place for couples and groups to relax between and after dances. Spanning two full stories it is topped by a skylight that bathed the room in soft yellows, ambers and golds. The lower half is centred by a double-sided fireplace around which the elaborate mahogany staircase wound its way up to the gallery. The vaulted ceilings on both floors were propped up by Gothic pillars, and coupled with the exquisite Gothic carvings in both stone and wood (notably the arched doorways and five similar cabinets), the whole was worthy of any Medieval castle or abbey.

A Favorite of the Governors-General

To gain some insight into the social hierarchy of Montreal in the 1880s, one has to look no further than the Tandem Club: who occupied which sleigh; with whom; and, in which order they progressed. In February 1884, R.B. Angus followed Andrew Allan (both driving four-in-hands) who was behind Baumgarten in his "magnificent" four-in-hand in which he was driving the future Earl and Countess of Minto, while they were led from the front by Lord and Lady Lansdowne's sleigh - the most magnificent, of course.

Baumgartens's ease around - and understanding of - the aristocracy, coupled with his generous nature and cultured mind made him a firm favorite with Landowne and Minto. Choosing to stay here over taking apartments at the Windsor Hotel, the Lansdownes (who already "entered fully into the life of the Montreal Hunt") stayed for ten days in January, 1887, and for a further week the following month during the Winter Carnival. By the time the Earl of Minto was appointed Governor-General of Canada in 1898, he warmly referred to Baumgarten as, "my old friend," and relished his invitations to McTavish Street.

War With Germany

In September, 1915, as the Canadian Expeditionary Force - with both his sons-in-law included - embarked for France, Baumgarten was perhaps the first in Montreal to hand over his mansion to the government for use as a hospital to soldiers sent back from the Front. But, despite all of this, anti-German sentiment had reached fever pitch and the man who Sir George Drummond had described just two years before as, "a man of excellence in every particular" was now forced to resign all his directorships (except from the all-powerful Bank of Montreal) when it became untenable to have German names on the boards of Canadian businesses, even though he was a Canadian citizen/British subject.

His old friends stuck by him, but many of the newer Anglo businessmen turned on him and he found himself on the receiving end of false and even preposterous allegations. A popular rumour that did the rounds was that he was secretly hiding Joachim von Ribbentrop at his country home in Ste.-Agathe-des Monts, while Ribbentrop was busy making a name for himself in the trenches. Regretfully, he stepped back from public life and retreated to his country home for the duration of the war. When peace was declared in 1918, he was still only sixty seven but had aged significantly and died the following year.

McGill & the Faculty Club

Mrs Baumgarten stayed on at McTavish Street with her daughters and sons-in-law until 1926 when she downsized to a terraced house on Richelieu Place. That year, she sold the mansion for a discounted price of $65,000 to McGill University to serve as the principal's official residence. The first and only principal to call it 'home' was General Sir Arthur Currie who the British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George had wanted to put in the place of Field Marshal Douglas Haig had the war continued into 1919 - high praise indeed.

General Currie died here in 1933 and with Canada firmly in the grips of the Great Depression, McGill sought a more cost effective home for the new principal. In the meantime, the house that been designed for entertaining was aptly transformed into the McGill Faculty Club. Sadly, the transformation saw the Gothic Gallery dramatically simplified and divided into two separate rooms: the billiard's room above, and the Dining Room below. But unlike the fate of so many like it, the house retains many of its original features and the McGill Faculty Club will soon mark the 100-years its enjoyed here.

His old friends stuck by him, but many of the newer Anglo businessmen turned on him and he found himself on the receiving end of false and even preposterous allegations. A popular rumour that did the rounds was that he was secretly hiding Joachim von Ribbentrop at his country home in Ste.-Agathe-des Monts, while Ribbentrop was busy making a name for himself in the trenches. Regretfully, he stepped back from public life and retreated to his country home for the duration of the war. When peace was declared in 1918, he was still only sixty seven but had aged significantly and died the following year.

McGill & the Faculty Club

Mrs Baumgarten stayed on at McTavish Street with her daughters and sons-in-law until 1926 when she downsized to a terraced house on Richelieu Place. That year, she sold the mansion for a discounted price of $65,000 to McGill University to serve as the principal's official residence. The first and only principal to call it 'home' was General Sir Arthur Currie who the British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George had wanted to put in the place of Field Marshal Douglas Haig had the war continued into 1919 - high praise indeed.

General Currie died here in 1933 and with Canada firmly in the grips of the Great Depression, McGill sought a more cost effective home for the new principal. In the meantime, the house that been designed for entertaining was aptly transformed into the McGill Faculty Club. Sadly, the transformation saw the Gothic Gallery dramatically simplified and divided into two separate rooms: the billiard's room above, and the Dining Room below. But unlike the fate of so many like it, the house retains many of its original features and the McGill Faculty Club will soon mark the 100-years its enjoyed here.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Connections

Be the first to connect to this house. Connect to record your link to this house. or just to show you love it! Connect to Baumgarten House →