McTavish Mansion

Mount Royal, Montreal, Quebec

Started in 1800 for the fur baron Simon McTavish (1751-1804), chief partner of the North West Company, whose personal estate at his death was valued at £125,250. On retiring from the fur trade, McTavish had moved to London where he planned to live out his days among English high society. But, his French-Canadian wife, Marie-Marguerite Chaboillez, grew homesick so they returned to Montreal and he built this mansion for her. Soon after the exterior was completed, his wife's brother-in-law, Lt.-Colonel Joseph Bouchette (1774-1841), described it as, “a large, handsome, stone building… at the foot of the mountain in a very conspicuous situation.” It sat amidst fields before roads had reached what would become Montreal's "Golden Square Mile," roughly just below today’s Pine Avenue, between Peel and McTavish Streets. But, McTavish did not live to see it completed and it sat empty - and supposedly haunted - for 60 years....

This house is best associated with...

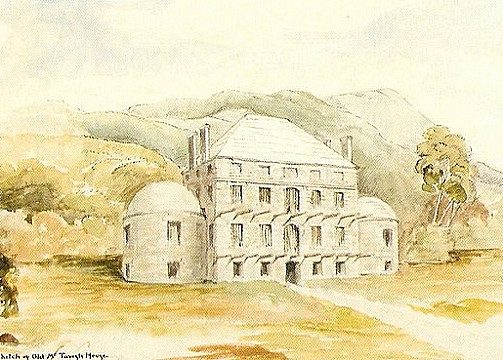

The mansion was constructed with dressed (cut) limestone by French masons. The central portion measured 60-x-45-feet, but it was flanked by two circular wings, each one extending 30-feet which gave the house an overall length of 120-feet - more than double the size of the Lafontaine House. These wings were capped by typically French, domed roofs, so that they resembled a pair of giant pepper pots. Each contained two large rooms with arched ceilings and many windows, and one was intended to be the dining hall.

The house stood over a "low-level" basement floor, although the ceiling was in fact 12-feet high and the basement was only dug out one foot below the ground. This floor, in a similar layout to that at Drayton Hall, was intended for the kitchen and servant’s quarters, but the windows here were "unusually high" and opened all the way to the ground. Above the kitchens were the two main floors intended for the family, and a further fourth floor for servants. There were four brick chimneys, and if completed the goods entrance to the basement visible in the picture would have been obscured by at least one flight of steps.

The Old Lion's Lair

The Old Lion's Lair

As one of the wealthiest, most revered characters in Montreal and the undisputed leader of its buoyant fur trade, McTavish was known as “the old lion of Montreal”. In reference to his grand style of living, the French nicknamed him “the Marquis”. His country estate covered the land from the Mount Royal Cemetery down to the Gare Centrale CN Station (formerly the Windsor Station). Its western boundary today would be about Stanley Street and its eastern boundary would have roughly been Mansfield Street. It stood about three quarters of a mile from Saint-Antoine Street which was then its nearest thoroughfare.

McTavish chose to build his mansion near the uppermost limit of his property. This position not only assured him of a magnificent view, it also ensured maximum visibility so his prosperity and position in society could be seen - and admired - by all. In those days, it was visible on the slopes of Mount Royal from any point in Montreal. In 1891, it was recalled that, "the front wall of the building stood about 20-feet along the lower line of the Braehead property. It was a few feet nearer Peel than McTavish Street (and) the largest part of the house stood on the property now owned by Andrew Allan (Iononteh)".

"The Haunted House"...

In 1804, the roof had just been laid and work on the lavish interior of the mansion was being finished when McTavish suddenly dropped down dead – brought on by a cold having spent so much time on site overseeing the construction of his house. His principal heir in Montreal was already happily installed at Chateau Saint-Antoine and so all work was brought to a standstill - nothing further ever being done except boarding up the doors and windows. Barrels of hardened plaster, which many years later were still to be seen lying among the floor-beams, testified to the abruptness with which the work had ceased. From then on it was referred to as “the haunted house” – a massive husk of a mansion that was never finished and only ever occupied - if the legends were true - by McTavish’s ghost.

From 1804 until its demolition in 1861, rumours ran rife about the “haunted house” whose empty vista loomed eerily over Montreal for sixty years. Those who passed it after nightfall swore to seeing McTavish’s ghost wandering through the ruins of his mansion. Others claimed they had seen creatures not of this world dancing upon the high roof, and white figures leaping in-and-out of the vacant cellar windows. On clear nights, in a particular phase of the moon, a ghostly figure was said to appear on the high tin-roof. Still further, some claimed to have heard moans and screams emanating from within its walls, and a gurgle, as if someone were dying of strangulation...

... Logically Explained

... Logically Explained

A file of documents on the McTavish house was collected by the notary Dakers Cameron and is held in the McGill Archives. It contains many affidavits, signed and attested, in which those who had known the McTavish house had set down their memories of it. It is also within these documents that the more fanciful ghost stories are explained:

A legend grew over the years that McTavish had hung himself from a beam in his unfinished mansion, but this was untrue - he died in bed of pneumonia brought on by a common cold. The place of his death was not his townhouse, but a comfortable 8-room, stone farmhouse he had leased a few hundred yards to the west of the mansion to better oversee its construction. In today's terms, the farmhouse stood on Drummond Street and it was demolished circa 1880 when Duncan McIntyre built Craigruie in its place.

In regards to the gurgling sound that people attributed to the legend, this in fact emanated from a rill which flowed under the house but was exposed during its demolition. The moans and the screams heard from within had been real, but they came from vagrants seeking shelter within its walls who wished to scare away intruders. The white figures seen leaping in-and-out of the cellar windows were in fact sheep grazing in the fields round and about. As for the apparitions on the tin-roof, it was a phenomenon created by a dazzling beam of moonlight on a certain angle of the roof at a certain hour.

Not Quite Gone...

In regards to the gurgling sound that people attributed to the legend, this in fact emanated from a rill which flowed under the house but was exposed during its demolition. The moans and the screams heard from within had been real, but they came from vagrants seeking shelter within its walls who wished to scare away intruders. The white figures seen leaping in-and-out of the cellar windows were in fact sheep grazing in the fields round and about. As for the apparitions on the tin-roof, it was a phenomenon created by a dazzling beam of moonlight on a certain angle of the roof at a certain hour.

Not Quite Gone...

As testament to the excellent construction of the McTavish house, after sixty years of non-occupancy, a plan had been devised by the architect John W. Hopkins (who designed Ravenscrag among other notable residences) to bring about its completion in 1860. As it was, the plans were abandoned, and the house was demolished in 1861.

The materials which had been used to build the McTavish home did not go to waste and a significant part of the old house was incorporated into Braehead, finished in 1862 for Orrin Squire Wood (1817-1909). Wood confirmed: “the (McTavish) house was removed in 1861 by the mason who built the new house (Braehead). All of the material of value in the old house was used in the new house, coach house, driveway and walks. The joice (first quality pine) from the old house was cut up by my carpenter, Mr Robert Weir, and used for doors, window frames and finishing in the new.” In this way, the house that still stands at the top of McTavish Street today is a tangible link with "old Lion's" mansion.

The New Merchant Princes

The New Merchant Princes

In 1844, the McTavish estate was sold for £30,000 to three gentlemen - there not being one man in Montreal then rich enough to buy it alone. By 1853, the portion that lay below Ste.-Catherine Street had been divided up into building lots (notably Prince of Wales Terrace) and sold. In 1860, an auction was held for the purpose of selling off the remainder of the estate from Sherbrooke Street up onto the mountain. Again, this remaining part of the estate was divided up, this time into five large plots to be sold off separately:

Unsurprisingly, the auction drew plenty of attention, but though John Frothingham (1788-1870) of Piedmont Hall was present, he did not bid and instead noted in his journal, “enormous prices I think, but people feel rich”. However, Plot 5 was purchased by Sir Hugh Allan (1810-1882) for £2,250, on which he built Ravenscrag. This 14-acre plot was directly above the McTavish house and continued for another 700-feet up the mountain.

Unsurprisingly, the auction drew plenty of attention, but though John Frothingham (1788-1870) of Piedmont Hall was present, he did not bid and instead noted in his journal, “enormous prices I think, but people feel rich”. However, Plot 5 was purchased by Sir Hugh Allan (1810-1882) for £2,250, on which he built Ravenscrag. This 14-acre plot was directly above the McTavish house and continued for another 700-feet up the mountain.

Plot 4 measured just 3,000 square feet, but it was the site of the ruins of the old McTavish house itself. Described as “a magnificent emplacement,” it was purchased by Lt.-Colonel Augustus Nathan Heward (1824-1866) for £2,650. Heward later sold it on to Sir Hugh’s brother, Andrew Allan (1822-1901), on which he built Iononteh in 1865. It is unclear who bought the remaining two plots, but certainly Braehead occupied one.

The McTavish Monument

The McTavish Monument

In the tradition of the Scottish lairds, McTavish requested that his funeral was to be held at the house, and he was to be buried there too. His nephews, William McGillivray (1764-1825), of Chateau Saint-Antoine and Simon McGillivray (1785-1840), built a 20-foot column under which he was buried a few feet to the south - enclosing the spot within a walled mausoleum. In 1820, John McGregor described the site as a, "retired and beautiful spot (accessed by) a pretty path (that) winds among the trees. During his lifetime, McTavish had come there frequently, spending hours sitting on the same spot reading.

McTavish's monument once occupied a prominent place in Montreal’s iconography. On building the perimeter wall to the west of Ravenscrag, Sir Hugh Allan was careful to respect the old lion's resting place, giving instructions that the wall be indented at that point rather than going straight through it. But, in 1942, rather than repair what was then Montreal’s oldest monument, the City of Montreal quickly tore the column down and replaced it with a small, inconspicuous block hidden among the trees before anyone could object. In 2007, Heritage Montreal suggested plans to re-erect the monument with plaques describing the influence McTavish had on Montreal. That plan remains on hold...

The Echo of the Lion's Last Roar

The Echo of the Lion's Last Roar

In his will, McTavish instructed that all four of his children were to be sent to England for their education. His widow, Marie-Marguerite Chaboillez, accompanied them in 1806. Two years later in London she married Major William Smith Plenderleath Christie (1780-1845), the eventual sole heir of his natural father General Gabriel Christie (1722-1799), one of the largest landowners in Quebec. In 1841 the Major built Manoir Christie at Iberville.

McTavish’s sudden death and the unfulfilled legacy that was his mansion did not end the tragedy that surrounded the end of his life. No doubt he hoped his family would complete the mansion after his death and that it would serve as the seat of the McTavishes of Montreal for generations ahead. As it was, work on the mansion was not continued and neither his wife nor any of his children were to return to Montreal. In 1818, his eldest son died, followed the next year by his two daughters. His last remaining child died in 1828. All of them succumbed in early adulthood, unmarried, without offspring. Thus ended the lofty aspirations of Simon McTavish the progenitor, "the old lion of Montreal".

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Connections

Be the first to connect to this house. Connect to record your link to this house. or just to show you love it! Connect to McTavish Mansion →