Glenclyffe

Glenclyffe, Garrison-on-Hudson, Putnam County, New York

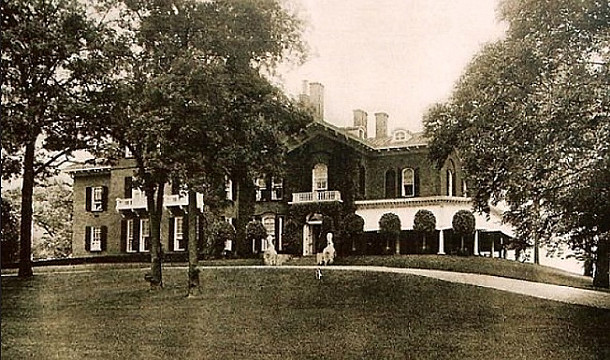

Built in 1857, for Eugene Dutilh (1814-1895) and his wife Susan Moore Laight (d.1893). However, the Civil War saw them relocate to England and their house was purchased and extended by Senator Hamilton Fish (1808-1893) whose family are best associated with Glenclyffe. Hamilton's daughter-in-law, the quick-witted, sharp-tongued society hostess "Mamie Fish" who strove never to be boring held many of her incongruous parties here. Located in the "Hudson Highlands" and set back from the banks of the Hudson River, the house has since been engulfed through a series of dramatic extensions since 1923 by what is today the Garrison Institute. The front door and window above is still recognizable, but otherwise it is almost impossible to see the old house....

This house is best associated with...

Stuyvesant Fish Jr. wrote in his memoirs, "my grandfather bought 'Glenclyffe' from a Frenchman, a Mr Dutilh, who built the house in the late 1850's, taking as his model a house he had seen and liked in the south". Eugene Dutilh had made his money importing silk. His wife was a daughter of Gen. Edward W. Laight, a distinguished New Yorker who was married to Ann Huger from a well-connected family in Charleston, South Carolina, whose brother lived at Huger House and sister-in-law grew up at Middleton Place.

In 1861, the Dutilh house and further land was purchased by Senator Hamilton Fish I. He was named for his parents' friend, Alexander Hamilton, and like his namesake he too became a political heavyweight. He was the 16th Governor of New York and at the end of the Civil War he was appointed Secretary of State in the cabinet of President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). He is considered by scholars to have been one of the most successful to hold that post due to his efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation. His wife, Julia, was known for her "sagacity and judgement" and grew up at Liberty Hall in New Jersey. They enjoyed a long happy marriage and were the parents of eight children.

The House & Estate

In 1861, the Dutilh house and further land was purchased by Senator Hamilton Fish I. He was named for his parents' friend, Alexander Hamilton, and like his namesake he too became a political heavyweight. He was the 16th Governor of New York and at the end of the Civil War he was appointed Secretary of State in the cabinet of President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). He is considered by scholars to have been one of the most successful to hold that post due to his efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation. His wife, Julia, was known for her "sagacity and judgement" and grew up at Liberty Hall in New Jersey. They enjoyed a long happy marriage and were the parents of eight children.

The House & Estate

The original house built for the Dutilhs was designed by the well-known architect Calvert Vaux (1824-1895) and bore a distinct similarity to one of his earlier designs, Beechwood. The Civil War directly affected Dutilh's business and he relocated to England. Hamilton Fish bought their house in 1861 and added to his landholdings by then acquiring the historic 480-acre estate on which Beverley House had stood from the Parrott family.

Having recently returned from a two-year tour of Europe, when Hamilton Fish enlarged his new house to 21-rooms (at a cost of $30,000) he stuck to the original Italianate style. Standing on the opposite bank of the river from West Point Academy, his mansion enjoyed sweeping views from the south-facing piazza across the lawns and down to the Hudson. The entrance to the estate was guarded by a gate lodge and the house (that he named Glenclyffe) was approached by a long carriage drive that passed through woods, expansive gardens, and finally up past the fountain pool planted with water lilies.

Having recently returned from a two-year tour of Europe, when Hamilton Fish enlarged his new house to 21-rooms (at a cost of $30,000) he stuck to the original Italianate style. Standing on the opposite bank of the river from West Point Academy, his mansion enjoyed sweeping views from the south-facing piazza across the lawns and down to the Hudson. The entrance to the estate was guarded by a gate lodge and the house (that he named Glenclyffe) was approached by a long carriage drive that passed through woods, expansive gardens, and finally up past the fountain pool planted with water lilies.

The enlarged mansion measured 16,000 square feet, containing 5-bedrooms, 6-bathrooms and 3-servant's rooms, though it was capable of sleeping a far greater number of bodies: In 1873, Fish wrote to his friend, Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), that he had a houseful of 30-people after his daughter, Susan Le Roy Fish (1844-1909), had been detained there with her husband, William Evans Rogers (1846-1913), and their young brood.

The principal reception rooms then included a drawing room, dining room, billiard room and library. Fish kept the majority of his extensive collection of books at Glenclyffe, ranging from old leather-bound sets of the classics to an always increasing number of new biographies and history books. Except for the works of Sir Walter Scott, Hamilton didn't care so much for poetry or fiction. The majority of his library was sold off at auction in 1925, but several individual books can still be found on the open market today.

Hamilton's Glenclyffe

Fish kept a notebook of the dinner parties he held and aside from a great many society names (Livingston, Duer, Astor, Schermerhorn, Cadwalader, Belmont etc.) he frequently enjoyed the company of the leading minds of the day, with men such as: Joseph Hodges Choate; Whitelaw Reid; Lloyd Bryce; Abram Stevens Hewitt (1822-1903); and, William Maxwell Evarts (1818-1901). If Hamilton found himself glued to his desk in Manhattan, in the country his life was the polar opposite:

The principal reception rooms then included a drawing room, dining room, billiard room and library. Fish kept the majority of his extensive collection of books at Glenclyffe, ranging from old leather-bound sets of the classics to an always increasing number of new biographies and history books. Except for the works of Sir Walter Scott, Hamilton didn't care so much for poetry or fiction. The majority of his library was sold off at auction in 1925, but several individual books can still be found on the open market today.

Hamilton's Glenclyffe

Fish kept a notebook of the dinner parties he held and aside from a great many society names (Livingston, Duer, Astor, Schermerhorn, Cadwalader, Belmont etc.) he frequently enjoyed the company of the leading minds of the day, with men such as: Joseph Hodges Choate; Whitelaw Reid; Lloyd Bryce; Abram Stevens Hewitt (1822-1903); and, William Maxwell Evarts (1818-1901). If Hamilton found himself glued to his desk in Manhattan, in the country his life was the polar opposite:

At Glenclyffe, where he had more leisure, he kept much outdoors. In 1877, his farmer and superintendent broke down, and not wishing to discharge the man, he assumed the work himself... He grew enough apples and small fruits to be liberal to his neighbours; he cut enough hickory wood for the fireplaces in Stuyvesant Square. He was proud of his flowers, and especially of his roses (he kept a large greenhouse on the property). Some bushes which he imported from England in 1878 proved the most beautiful he had ever seen, and he was greatly gratified when his neighbour Osborn - of Castle Rock - remarked, "Well, heretofore I have been ahead of you in roses, now you have beaten me".

He walked, drove, blistered his hands with a pitchfork, and talked with the stream of visitors. When the day's work was done he delighted to sit on the south piazza enjoying the resplendent view down the river in the rich sunset light and watching the "Mary Powell" as she throbbed northward to Albany. On the north piazza hung a thermometer which he made it a rule to examine thrice daily, the last time just before going to bed; and he neatly entered the temperatures in red and black ink in large volumes.

In 1893, Hamilton Fish died at Glenclyffe having outlived his wife by six years. Glenclyffe was left to the eldest of his three sons, Nicholas Fish II (1846-1902). Nicholas had been both U.S. Ambassador to Switzerland and Belgium but since 1887 had returned to New York, mainly dividing his time between Manhattan and his other home in Tuxedo Park. In 1902, he was infamously murdered having been struck on the back of the head while leaving a saloon bar in which he'd been entertaining two women of dubious repute!

Murder followed by a Mammoth Expansion

Murder followed by a Mammoth Expansion

Following the murder of the eldest brother and with the next brother happily ensconced at nearby Rock Lawn, Glenclyffe came into the possession of the youngest brother, Stuyvesant Fish (1851-1923), who was married to the infamous "Mamie" Fish (1853-1915).

Stuyvesant and Mamie Fish had then recently completed Crossways in Newport where she held court as one of the leading three society hostesses of her day. Owing to her position, she felt Glenclyffe was too small and in what must have been in or soon after 1902, the house was literally doubled in size to 32,000 square feet. The latest extension continued the original Italianate theme, but the interior - except for the library - was completely remodelled. Outside, the stables were expanded to hold 25-carriages.

Stuyvesant and Mamie Fish had then recently completed Crossways in Newport where she held court as one of the leading three society hostesses of her day. Owing to her position, she felt Glenclyffe was too small and in what must have been in or soon after 1902, the house was literally doubled in size to 32,000 square feet. The latest extension continued the original Italianate theme, but the interior - except for the library - was completely remodelled. Outside, the stables were expanded to hold 25-carriages.

Much of the extension included new servant's quarters including a new kitchen and pantry that allowed for the original reception rooms - dining room, morning room and conservatory - to be expanded. A ballroom was also added and on its completion the revamped mansion now consisted of 15-bedrooms, 13-bathrooms and 15-servant's rooms. The interior walls were panelled in oak and painted cream.

Stuyvesant's Glenclyffe

Glenclyffe was the favorite of Stuyvesant's three mansions. Though amused by his wife's antics, he himself cared little for high society and preferred the tranquility of his country estate, keeping it open year-round. He tended to avoid Crossways if he could and he even banned his sons from spending more than only a few days of "the season" at Newport. When Stuyvesant had guests at Glenclyffe, he took a hardy pleasure in showing them the plain, old-fashioned bedroom without running water that as a boy he had shared with his brothers: "None of the maids will sleep in it... it's not good enough for them; yet I spent some of the happiest hours of my life here"!

...and Mamie's

Stuyvesant's Glenclyffe

Glenclyffe was the favorite of Stuyvesant's three mansions. Though amused by his wife's antics, he himself cared little for high society and preferred the tranquility of his country estate, keeping it open year-round. He tended to avoid Crossways if he could and he even banned his sons from spending more than only a few days of "the season" at Newport. When Stuyvesant had guests at Glenclyffe, he took a hardy pleasure in showing them the plain, old-fashioned bedroom without running water that as a boy he had shared with his brothers: "None of the maids will sleep in it... it's not good enough for them; yet I spent some of the happiest hours of my life here"!

...and Mamie's

During autumn and spring, Mamie would usually have 20-house guests to stay over each weekend. She often referred to her husband as "The Good Man" and good-natured he certainly was. Despite his lack of interest in the frivolities of the Gilded Age (so enjoyed by his wife) he would often return from work in New York to find a party in full swing at Glenclyffe. He was frequently heard to say: "It seems I am giving a party. Well, I hope you are all enjoying yourselves" and, with that he would quietly retire to his library!

In Mamie's constant quest to rid the world of the mundane, she often invited the husband and wife duo, Vernon and Irene Castle, to invigorate the dances held at Glenclyffe by teaching her guests the latest fashions. Irene recalled: "The house was fantastically costly and far too dressy with its masses of gilt and old rose and paintings and velvet portieres. It bustled with manservants in striped pants and short pea jackets covered with braid".

Each year. Mamie held a Halloween party for both guests and servants: she and her party danced in the ballroom while her servants and their guests danced in the stables. Just as at Crossways, she revelled in concocting elaborate entertainments for her guests though at Glenclyffe they often had an "olde worlde" country theme...! In 1912, two typically incongruous parties held in different seasons were written-up in The New York Times:

June 8: Mrs Stuyvesant Fish is giving a house party over the weekend and on Sunday at Glenclyffe, Garrison-on-Hudson. One of the features was a lawn party, which was attended by the hostesses of several other house parties at adjoining estates who also brought their guests to Glenclyffe. The lawn party entertainment began with the arrival of the Morris Dancers in an old-time cart filled with hay and drawn by oxen and preceded by bagpipers. The Morris dancers did a series of Scotch dances, reels, and hornpipes, and afterwards tea was served on the broad verandahs. Tonight there will be a large dinner, to which several of the hostesses will bring their guests.

October 20: Mrs Stuyvesant Fish gave a small and informal dance last night at Glencylffe Farm, Garrison, following the annual horse show there. The guests included the house party there over the week-end and a number of the Garrison colony with their house guests. The huge hall was decorated with Autumn leaves, wheat and jack-o-lanterns, and Japanese lanterns were festooned throughout the grounds. The affair was like an old English harvest festival, with Scotch dances and bagpipe music, and the supper was served at midnight.

Glenclyffe Institutionalized

Both Mamie and Stuyvesant Fish died at Glenclyffe, the latter outliving his wife until 1923. That year, their children sold the estate to the Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order for $150,000 and by the following year Glenclyffe had been transformed into a high school run by them. Towards the end of the 1920s, an east wing was added to the mansion containing a gym, chapel and further dormitories. In 1930, a west wing was added to house the nuns who cooked and cleaned for the school. A further vast extension was made to the house (now almost unrecognizable except for the front entrance) in 1961, before the school closed its doors in 1974.

Both Mamie and Stuyvesant Fish died at Glenclyffe, the latter outliving his wife until 1923. That year, their children sold the estate to the Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order for $150,000 and by the following year Glenclyffe had been transformed into a high school run by them. Towards the end of the 1920s, an east wing was added to the mansion containing a gym, chapel and further dormitories. In 1930, a west wing was added to house the nuns who cooked and cleaned for the school. A further vast extension was made to the house (now almost unrecognizable except for the front entrance) in 1961, before the school closed its doors in 1974.

From 1975 to 1988, it served as a convent to the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. In 2001, for $7.4 million, the Open Space Institute purchased the estate which by then included both the former mansion and "The Friary" erected as a subsidiary building in 1932. Today the Glenclyffe estate and buildings is operated by the Garrison Institute.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Connections

There is 1 member connected to this house, are you? Connect to record your link to this house. or just to show you love it! Connect to Glenclyffe →

John J. Flanagan lives in Glenclyffe