Mary Mason Jones Mansion

1 East 57th Street, Manhattan, New York

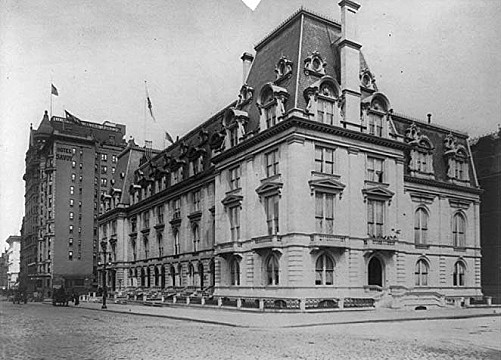

Completed in 1869, for Mrs Mary (Mason) Jones (1801-1891), the widow of Isaac Jones (1795-1854) - great-uncle of the great author, Edith Wharton. Her house may be gone, but Edith immortalized her formidable great-aunt as "Mrs Manson Mingott" in her book, The Age of Innocence. Built on land inherited from her father at a time when fashionable society was still living 20-blocks south, Mary's mansion was an intentional showpiece. The Italianate marble A.T. Stewart Mansion was completed in the same year (20-blocks south of course), but - pre-dating the Vanderbilts - hers was the first marble chateau put up in Manhattan. "Marble Row" as it was also known was home to a succession of three of the most socially ambitious hostesses in Gilded Age history....

This house is best associated with...

In 1839, Mary's husband, Isaac Jones, succeeded her father, John Mason, as President of the Chemical Bank and in their day both men were considered among the wealthiest merchants in New York City. The Jones' then lived at 734 Broadway and the houses on either side of them were occupied by Mary's sisters, Rebecca and Sarah. Invisible to the passer-by, each of their Drawing Rooms opened up on to the other to create what was then the city's longest ballroom. From this base on Broadway - in the decade before the Mrs Astor - the Mason sisters held court and Mary, the eldest, reigned supreme.

Rumor has it that in his final moments on this earth, old John Mason was barely conscious in a chair when two of his daughters (Mary?!) and their husbands trussed him up and sandwiched him between a board and the chair-back. Now unable to slump forwards, they succeeded in guiding quill-to-paper, signing what was apparently "his will". Given the circumstances, it may not surprise you to hear that there were a few objections to "his will" and the ensuing legal proceedings were dragged through the courts for 15-years before the dust finally settled. By that time (1854), Mary's husband was dead, but courtesy of Daddy-dearest she now owned a vast - and soon to be a very valuable - tract of land covering two city blocks from Fifth Avenue to Park Avenue, between 57th and 58th.

"The Crowning Touch to her Audacity..."

Mrs Jones had a taste for luxury, she was already the first person to have had gas and a private bathtub installed in her new marital home on Chambers Street back in 1818 and if her private box in the Park Theatre was anything to go by (upholstered in blue silk with silver, not metal, railings), you knew this dowager wasn't going to be planning anything ordinary to grace her new neck of the woods. And, neither could it be: she was acutely aware that large as her landholding was, it was also 20-blocks north of what was then deemed "fashionable-living," her father having acquired it back in 1823 as a future investment for what would prove a steal at $10 a lot!

In 1867, drawing on the France she already knew and loved (her elder daughter, Mary, had married a French Baron in Paris 20-years before), she worked with architect Robert Mook to produce a revolutionary new vision for old New York, straight from the architectural books of an even older Europe: Loosely inspired by the likes of the Chateau de Fontainebleu and in many ways resembling an ‘Hotel de Ville’ (a French Town Hall), the shimmering white marble chateau they produced was completed in 1869. It shone out like a beacon amid the row upon rows of brownstone favored by old Knickerbocker society and it drew precisely the right amount of awe that architect and client had hoped to inspire.

"Watching Calmly for Life and Fashion to Flow..."

In "the wilderness" as it then was, Mary was clever not to have created one solitary castle from which to rule. "Marble Row," as her creation was christened, was in fact a series of individual residences and she took up in the east corner, addressed 1 East 57th Street.

If you've read Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence you may remember the rather superbly named "Mrs Manson Mingott," modelled on none other than Edith's great-`aunt, our very own Mrs Mary Mason Jones:

(Mrs Mary Mason Jones/Manson Mingott) put the crowning touch to her audacity by building a large house of cream-coloured stone... it was her habit to sit in a window of her sitting-room on the ground floor, as if watching calmly for life and fashion to flow northward to her solitary doors. She seemed in no hurry to have them come, for her patience was equalled by her confidence. She was sure that presently the hoardings, the quarries, the one-story saloons, the wooden green-houses in ragged gardens, and the rocks from which goats surveyed the scene, would vanish before the advance of residences as stately as her own - perhaps (for she was an impartial woman) even statelier.

Her house was briefly described in 1884 on the occasion of her great-granddaughter's introduction to New York Society: "The halls of the large house last evening were filled with palms and rare exotic plants. Broad steps ascend from the square hallway as one enters and leading to the second floor terminate at the entrance to a large ball room… it is a large square room, with high ceiling and furnished with brightly colored upholstering... on one side is a reception room (and) on the first floor is the suite of parlors."

"There is One House Mrs Stevens will Never Enter..."

The widowed dowager continued to entertain as she had done on Broadway, filling her house with New York's ageing upper crust, all the while watching while the city grew progressively north and the value of her property rose with it. But, if there was one thing her blue blood could not abide, it was the parvenus who rode this wave of rapid growth and in her eyes threatened to disrupt the old-world decorum of her inner sanctum.

To Mrs Jones, no-one better represented this dreaded new breed of person than the redoubtable Mrs Marietta (Reed) Stevens (1827-1895). Her obituary said of her: "Probably no woman conspicuous in New York society has been more talked about than Mrs Stevens". Loved by her friends and loathed by her enemies, she spent a lifetime dividing opinions. The daughter of a greengrocer who made it big and then entered local politics, she was an unapologetic social climber and to the horror of society had started by marrying a millionaire 25-years her senior! Her husband, "the best judge of wines in the country" was the kindly old and popular hotelier, Paran Stevens (1802-1872).

The widowed dowager continued to entertain as she had done on Broadway, filling her house with New York's ageing upper crust, all the while watching while the city grew progressively north and the value of her property rose with it. But, if there was one thing her blue blood could not abide, it was the parvenus who rode this wave of rapid growth and in her eyes threatened to disrupt the old-world decorum of her inner sanctum.

To Mrs Jones, no-one better represented this dreaded new breed of person than the redoubtable Mrs Marietta (Reed) Stevens (1827-1895). Her obituary said of her: "Probably no woman conspicuous in New York society has been more talked about than Mrs Stevens". Loved by her friends and loathed by her enemies, she spent a lifetime dividing opinions. The daughter of a greengrocer who made it big and then entered local politics, she was an unapologetic social climber and to the horror of society had started by marrying a millionaire 25-years her senior! Her husband, "the best judge of wines in the country" was the kindly old and popular hotelier, Paran Stevens (1802-1872).

Mrs Jones had long made it her habit to host French-style salons where guests might hope to glean some culture from the artists and writers invited to mix among the crowd. Not only did Mrs Stevens and her "magnetic personality" dare to up the ante by hosting refreshingly alternative musicales with the choicest wines and champagne; but, in order to eliminate the prospect of rival invitations - to the horror of Mrs Jones - her musicales took place on Sunday evenings when traditional Knickerbocker society was supposed to be at home with their families! It didn't happen overnight, but not before long Mrs Stevens', "position as a hostess was unassailable".

Churlishly - and as it would turn out most foolishly - Mrs Jones laid down the gauntlet by stating very publicly: "There is one house (her own on Marble Row) that Mrs Stevens will never enter. I am old enough to please myself, and I do not care to extend my sufficiently large circle of acquaintances". Given another chance, she'd probably not have said that...

"Grandmamma's Reproachful Spirit"

If Mrs Jones had bided her time to watch her corner of Manhattan become fashionable (which it most certainly did), then Mrs Stevens took a leaf out of her book to serve her revenge: On May 29th, 1891, Marietta almost certainly treated herself to the finest bottle of champagne in her late husband’s collection. At 90-years old, her arch-nemesis, Mrs Mary Mason Jones, was finally dead and with a spring in her step, she may hardly have been able to have contained her glee when she stepped into her Realtor’s office and slapped down what was required to see her name on the lease of the house, “Mrs Stevens will never enter”! Nonetheless, one of the deceased's grandchildren later admitted, "I assure you I was actually afraid to give my consent to the lease. I felt that I might be visited by Grandmamma's reproachful spirit"!

Having had the house completely 'de-Jonesed' and renovated to her own tastes, Mrs Stevens gave, "some of the finest dinners; her wines are of the best; her chef has few superiors, and her hospitality is unbounded... being the owner of the Victoria Hotel she (also) has a large interest in the management of the Fifth Avenue".

Mrs Stevens had achieved her reign over society against all the odds, and the likes of Mrs Jones had been formidable opponents. Comfortably ensconced in her rival's mansion, she could sit back and take pleasure in her achievements: she was known to all as a revered hostess of New York society; her beautiful daughter, Lady Paget, was mixing in the smartest circles in England; her grand-daughter, Louise, was the god-daughter of no less a figure than England’s King Edward VII; and, somewhat ironically, she had nearly become related to Mrs Jones when her son Harry had become engaged to Mrs Jones' celebrated grand-niece, Edith Wharton.

Mrs Stevens had achieved her reign over society against all the odds, and the likes of Mrs Jones had been formidable opponents. Comfortably ensconced in her rival's mansion, she could sit back and take pleasure in her achievements: she was known to all as a revered hostess of New York society; her beautiful daughter, Lady Paget, was mixing in the smartest circles in England; her grand-daughter, Louise, was the god-daughter of no less a figure than England’s King Edward VII; and, somewhat ironically, she had nearly become related to Mrs Jones when her son Harry had become engaged to Mrs Jones' celebrated grand-niece, Edith Wharton.

Marietta entertained until the end, giving a salon concert with the 60-strong Boston Symphony Orchestra and hosting a reception for 150 in the second floor ballroom for the Duke and Duchess of Veragua. But, perhaps "grandmammas reproachful spirit" had lingered on in her mansion: Just four years later, she suffered a fatal stroke with the news of the collapse of her primary source of income, the Fifth Avenue Hotel.

Bird-Watching at "Palace Corners"

Soon after Marietta’s death, the entire chateau was purchased by Hermann Oelrichs and his wife, another socially ambitious hostess, Tessie Fair. Tessie was the estranged daughter of - but co-heiress to – "Slippery Jim" and his fast-made millions. Hermann was no slouch either, worth a cool $52 million from shipping, and employing Stanford White, the Oelrichs' converted the chateau into one sole residence. Having completed those works in 1897, White got to work on their summer home in Newport home, Rosecliff, another white shimmering masterpiece.

Bird-Watching at "Palace Corners"

Soon after Marietta’s death, the entire chateau was purchased by Hermann Oelrichs and his wife, another socially ambitious hostess, Tessie Fair. Tessie was the estranged daughter of - but co-heiress to – "Slippery Jim" and his fast-made millions. Hermann was no slouch either, worth a cool $52 million from shipping, and employing Stanford White, the Oelrichs' converted the chateau into one sole residence. Having completed those works in 1897, White got to work on their summer home in Newport home, Rosecliff, another white shimmering masterpiece.

Standing at an intersection that now included several of the city’s most jaw-dropping mansions, The New York Times dubbed the enclave into which the Oelrich’s had bought, "the Palace Corners". With room to spare, they were joined in their new home by Tessie's popular, and as yet unmarried, younger sister, Birdie, who quickly caught the eye of their neighbor across the street, Willie K. Vanderbilt II.

Birdie and Willie were engaged by the following year (1898). Their wedding reception was held at the Oelrichs' chateau on which they lavished every attention to make sure it was one to be remembered. The crowds that gathered outside that day whipped themselves up into such a frenzy with the ostentatiousness of it all that the bride and groom could not reach their carriage and the policemen used their batons to clear a path for the increasingly irate newly-weds!

Unlike his wife, Hermann had little time for high society. By 1906 he had taken to living on his farm near San Francisco leaving Tessie to reign over New York while he managed her Californian inheritances. Despite the change in living arrangements, they remained close and Tessie was devastated when he died after having over-exerted himself, tirelessly helping the victims of the San Francisco Earthquake that struck that year. His funeral was held in their double Drawing Room on Fifth Avenue.

Unlike his wife, Hermann had little time for high society. By 1906 he had taken to living on his farm near San Francisco leaving Tessie to reign over New York while he managed her Californian inheritances. Despite the change in living arrangements, they remained close and Tessie was devastated when he died after having over-exerted himself, tirelessly helping the victims of the San Francisco Earthquake that struck that year. His funeral was held in their double Drawing Room on Fifth Avenue.

The Final Chapter

Tessie continued to divide her time between here and Rosecliff in Newport. In a futile attempt to separate herself from the encroaching stores and high-rise blocks that were gradually devouring the neighborhood's mansions, she surrounded the chateau with a wrought iron fence in 1911. By the conclusion of the First World War in 1918, she conceded that she was not the only one to have lost a war - her own to commerce - and by way of surrender she decamped further north.

The New York Trust Company moved in, purposefully maintaining its grand interior to give their clients a "home-from-home" feeling: "The dining room, which will be used for the general banking business is finished in panelled oak, and oak counters will be put in. The bookkeepers will have the ballroom, the library will be used as the ladies’ room, the parlor for the trust department, and the remaining rooms for consultations".

A matter of weeks before the Wall Street Crash in 1929, the Trust announced their plan to replace what remained of the marble chateau with a 15-story office block. It was gone the following year, and the address from where all those grand ladies once bagged their places in society is the same where today's grand ladies go to shop for bags: Louis Vuitton.

You May Also Like...

Categories

Styles

Share

Connections

Be the first to connect to this house. Connect to record your link to this house. or just to show you love it! Connect to Mary Mason Jones Mansion →